South San Francisco Unified School District (SSFUSD) rolled out a new curriculum in the 2023-24 school year designed to elevate the teaching and learning of science across all its elementary schools.

“Our goal this year is to ensure that every single student gets access [to science learning], and our hope is that as teachers see the engagement that the kids have—and the excitement that they have—that then it’s going to build on itself,” said SSFSUD’s Director of Innovation Jason Brockmeyer.

Not only does the new curriculum align with Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) developed in 2013, but it was chosen because of the way it shifts the responsibility for learning from teachers to the students themselves.

“The real shift is that kids are making sense of their learning,” said SSFUSD Curriculum and Instruction Specialist Jennifer Rosse, who has been the district’s point person for the adoption of new curriculum over the last five years. “It’s not explicit direct instruction. It’s a series of guided activities where students are constructing their own knowledge and learning.”

The new approach has required the district to invest in new equipment and materials, while also providing elementary school teachers with additional time to prepare lessons.

According to Brockmeyer, that was one of the reasons SSFUSD contracted with Legarza Sports to provide dedicated physical education instruction to elementary schools this year.

“There’s a need across the board for elementary teachers to have planning time,” said Brockmeyer, “so science was really kind of the driving force behind that.”

Hands-On Learning

Removing barriers to allow teachers time to prepare their classrooms for hands-on learning through science helps teachers and benefits students.

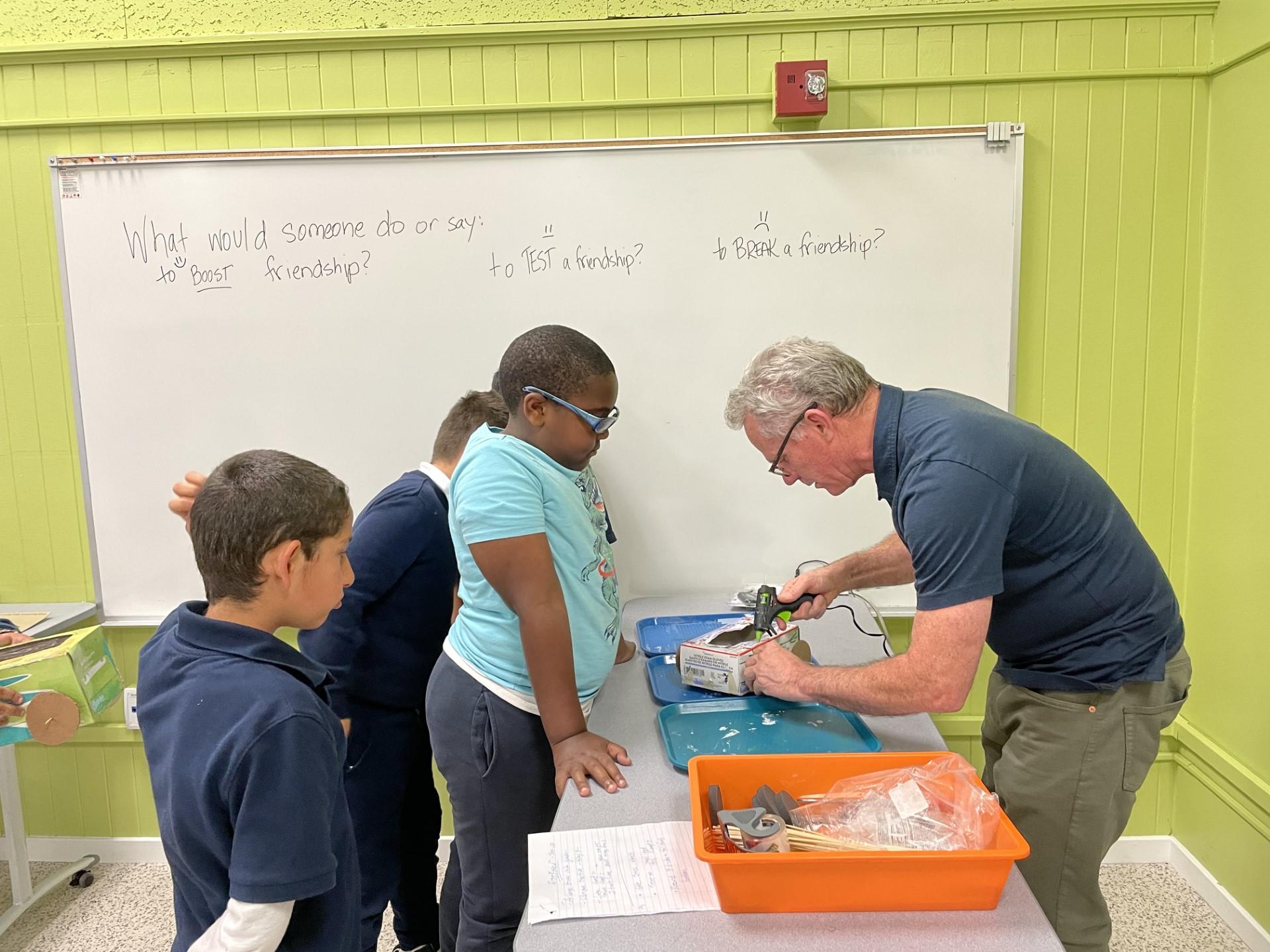

At Skyline Elementary on Friday, third grade teacher Julie Ulmer was guiding her class through a lesson about electromagnets and maglev trains.

“We’re trying to make a ride that’s like a maglev train,” said third grader Joelianna Estepa. “A maglev train in Shanghai uses an electromagnet. Electromagnets can be turned off and turned on. When it’s turned on, it makes the train levitate.”

Ulmer, who’s worked at Skyline for eight years, said she loves teaching science, because every student is engaged.

“Anything that’s really hands-on—they are the most engaged, and that to me is the way we get our future scientists excited about being in that world—in the STEM world—and we need more kids from our communities in that line of work and excited about it in third grade.”

Eight-year-old Arella Aguas seemed to agree.

Eight-year-old Arella Aguas seemed to agree.

“Last year we did not do experiments, but I didn’t know experiments could be this fun,” said Aguas.

Ulmer was part of a group of teachers who tested out or piloted the new science curriculum before the district officially adopted it.

Ulmer was part of a group of teachers who tested out or piloted the new science curriculum before the district officially adopted it.

She said she was looking for a curriculum that was heavy with hands-on projects and light on scientific jargon.

“For them to find the solutions on their own and come to their own conclusions is the best way for them to learn,” she said.

However, Ulmer said she still needs to tweak the lessons now and then by having students present and share what they’ve done, because it keeps them engaged and accountable.

Real-World Relevance

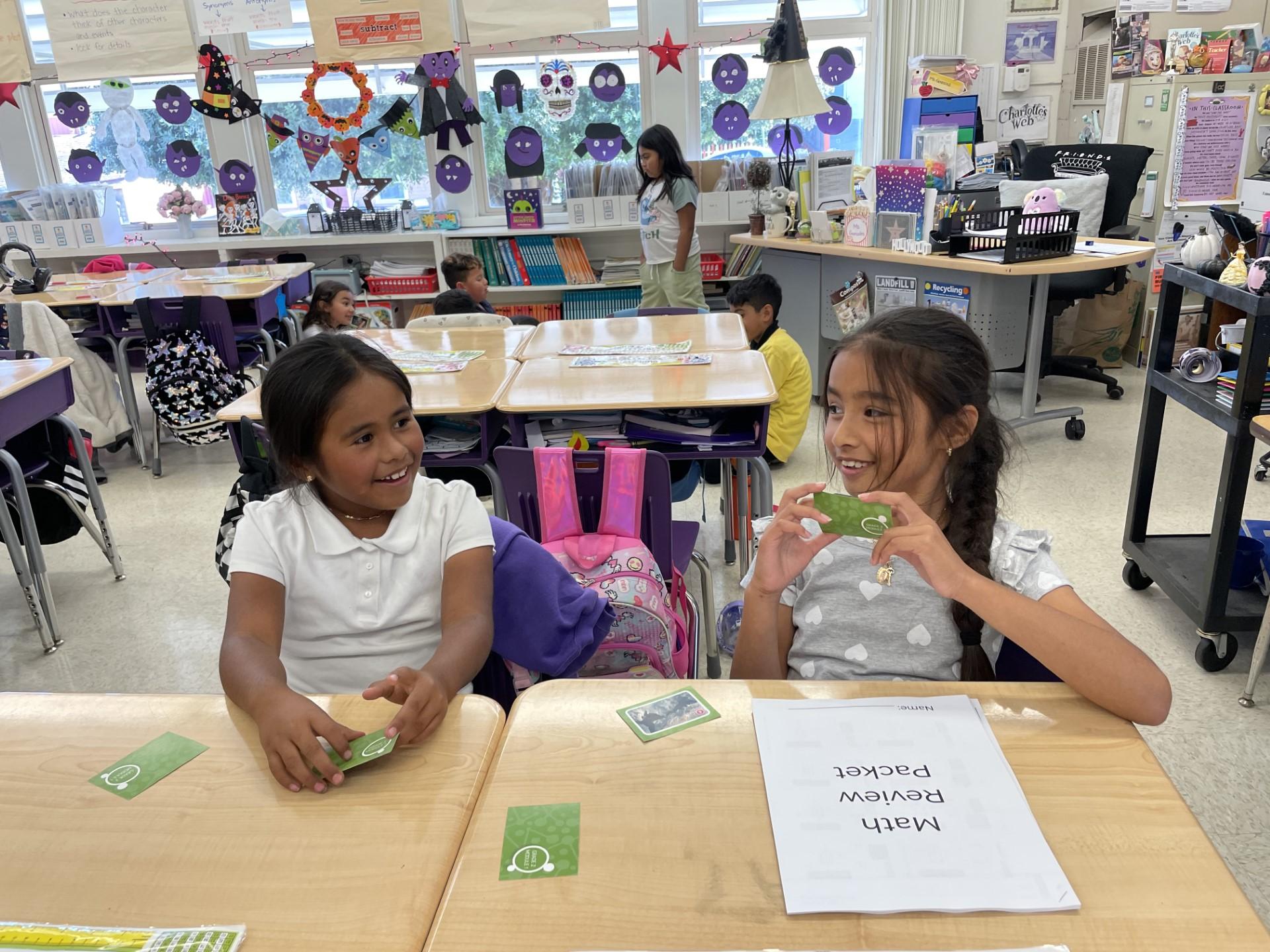

At Martin Elementary School, Charlotte Gonzales’s second grade class has been learning about land forms using Play-Doh.

“Science is always interesting, because it always tells us stories and helps us to learn things,” said second grader Luciana Arango-Betancur.

Gonzales, who’s been at Martin Elementary for eight years, has fully embraced the new curriculum.

She said the district’s previous curriculum had become outdated, which is why she also volunteered to pilot the new science curriculum before it was officially adopted.

This allowed her to see how the lessons connected to things in the real world, making them more relevant to students.

She said she likes how the new curriculum is structured and provides time for students to reflect.

“It gives a lot of time for collaboration,” Gonzales said. “They get to talk with one another. They get to work on their speaking skills, their listening skills, even just taking turns having different roles in whatever lesson that we’re in.”

Collaboration

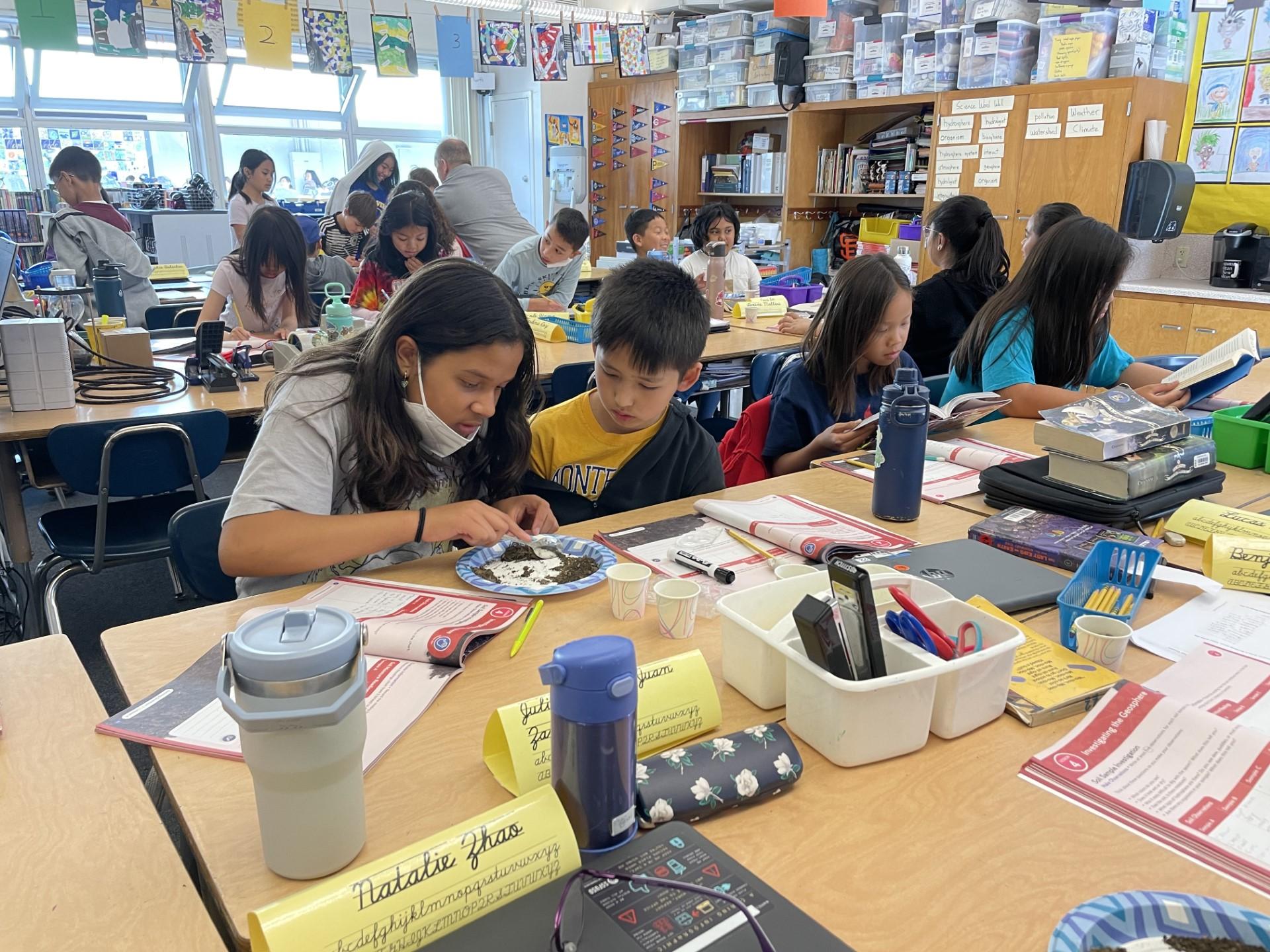

There was certainly a lot of talking and collaborating happening in Spruce Elementary fourth grade teacher Paul Summers’s class and in Michael Stewart’s fifth grade class at Monte Verde Elementary.

At Monte Verde, Mr. Stewart’s students were analyzing dirt samples taken from different areas of the school.

At Monte Verde, Mr. Stewart’s students were analyzing dirt samples taken from different areas of the school.

|

|

“We already did the hydrosphere, we already did the biosphere, and we already did the atmosphere,” said Stewart, “so today we’re working on the geosphere, and so what they were looking for is did they see water in the soil—was there life.”

Stewart has taught at Monte Verde Elementary for 20 years and functions as a de facto science teacher for all the school’s fifth graders.

Stewart has taught at Monte Verde Elementary for 20 years and functions as a de facto science teacher for all the school’s fifth graders.

“Because there’s so much set-up for science. . .it’s easier to bring the kids in with everything pre-set up than it is to set it up three times a day in three different classrooms,” he explained.

Fifth grader Nicholas Beuzenberg said that although science isn’t his favorite subject, he still enjoys it.

“It was fun. We got to see cool things too,” said Nicholas. “With the hand lenses we got to see—like— rollie pollies and the dirt how it looks and stuff.”

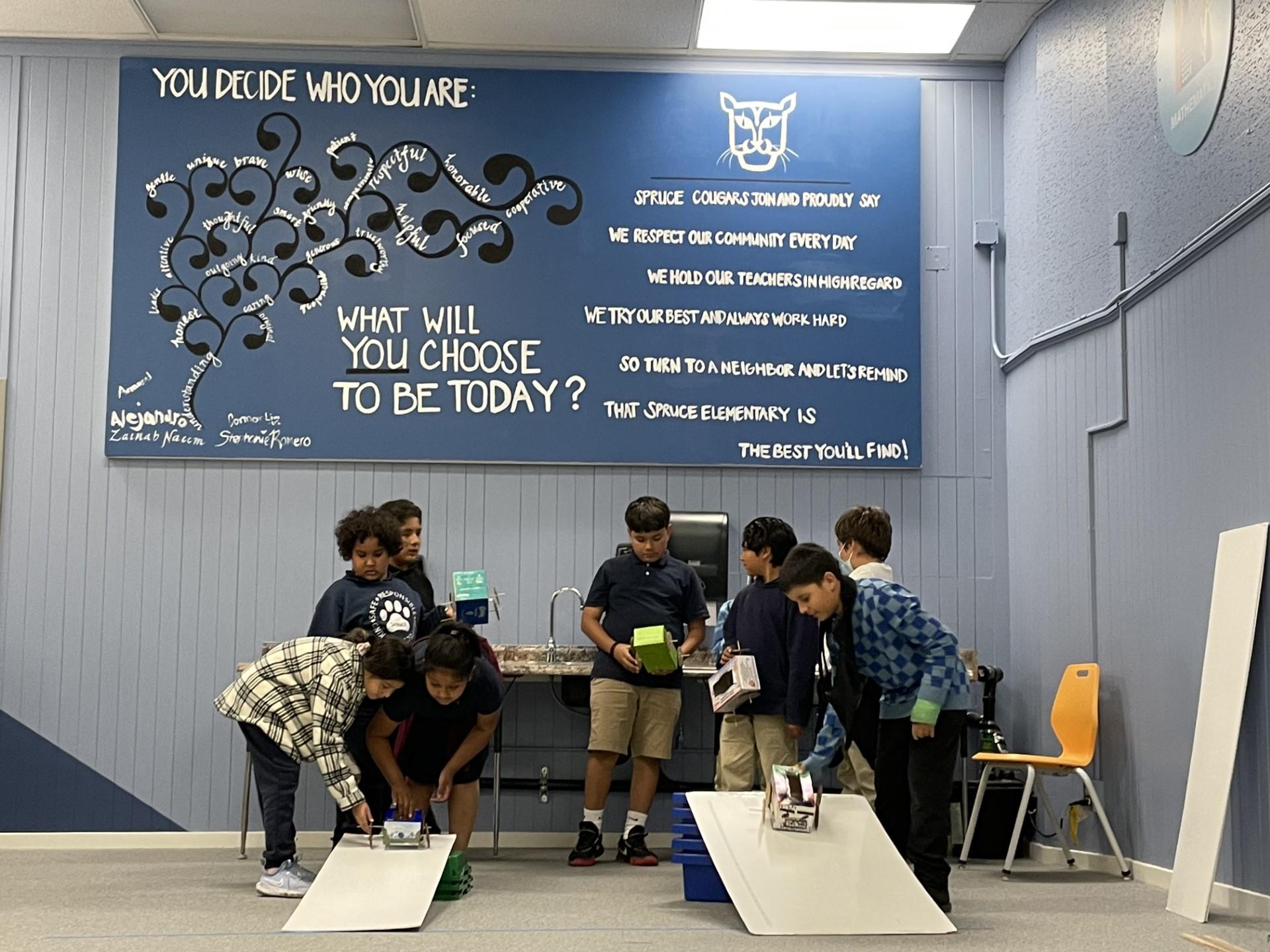

Meanwhile, students at Spruce were teaming up to build and test cars made out of shoe boxes, hot glue, and cardboard.

“We’re going to try crashing each other’s cars with eggs in it to try to protect the egg,” said Spruce fourth grader Elsa Mau. “We get to learn about how energy works, and we’re getting the chance to build something.”

Some teams with slower moving cars made adjustments to try to get more speed.

Some teams with slower moving cars made adjustments to try to get more speed.

“The wheels were bent, and then we fixed them,” said fourth grader Zachary Brevner.

Both Stewart and Summers identified the process of experimentation as something that captured the imagination of their students.

“The majority of the science students who have never experienced it really get the wonder,” said Stewart.

Summers concurred.

“They’re learning to work together, cooperating, collaborating, testing things. If something fails, that’s fine, you try again and redesign it,” he said.

Experimentation is the process of learning from failure, and it’s a concept that can help students succeed both in science and in life.